THE Awami League-led government seems to have become more aggressive than it was in its previous tenure about finalising and signing agreements, and implementing big projects in the energy and power, and transport and communications sectors. Expensive and risky projects, sometimes clearly against national interest, are being finalised without any parliamentary discussion or public consultation, any consideration of the consequences, and importance given to criticism and/or opinion from independent experts. Who are making decisions about these projects? How are these projects selected? Most importantly, why is such haste?

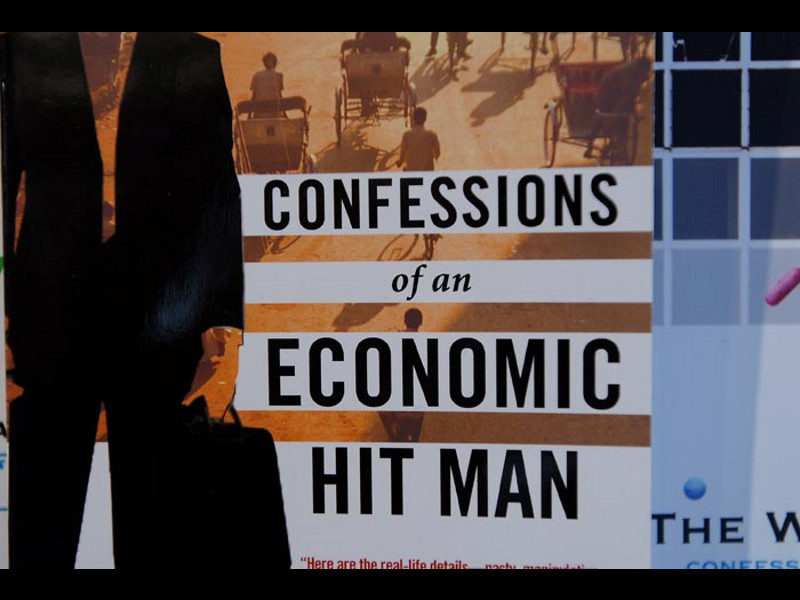

In Confessions of an Economic Hit Man (2004), John Perkins first defined ‘economic hit men’ as ‘highly paid professionals who cheat countries around the globe out of trillions of dollars’ and ‘funnel money from the World Bank, the US Agency for International Development (USAID), and other foreign “aid” organisations into the coffers of huge corporations and the pockets of a few wealthy families who control the planet’s natural resources.’

The tools that the economic hit men use, writes Perkins, ‘include fraudulent financial reports, rigged elections, payoffs, extortion, sex, and murder.’ ‘They play a game as old as empire, but one that has taken on new and terrifying dimensions during this time of globalization,’ he adds.

It is little wonder then that global companies spend more on advertisements or public relations activities, and lobbyists or economic hit men, than they do on research and development. Economic hit men seem to bring more corporate success than research does.

It would not be difficult to spot economic hit men in ministries, high-level meeting and late-night parties that feature key policymakers. A lot of consultancy reports and feasibility studies have piled up in ministries to justify predetermined projects. Corruption, commission and company men determine the course of actions of many policymakers. ‘No’ becomes ‘yes’ and disasters are masked as development. Eventually, these manipulated projects appear as ‘development’ projects in the budget document, included in the government’s priority list. Costs of public projects go up to cover the commissions, bribe and public relations expenditure.

If these are not the cases, how can one justify the project to destroy Sundarban, the project to kill rivers and wetlands, the project to evict millions of women and men, the project to increase national indebtedness, the project to increase energy vulnerability, the project to marginalise or degrade national capabilities, the project to make education and health care expensive commodities?

It has been learnt from newspaper reports and other sources that international oil companies have started PR activities to have more onshore blocks for gas exploration in Bangladesh, which was been kept for national agencies earlier. It seems that they have received some green signal from the government.

What has been our experience with the old onshore production sharing contracts? Facts and figures do not match with the propaganda. Some facts are given below:

1. Privatisation and bringing international oil companies into the energy sector has increased public expenditure instead of ‘reducing drainage of public resources’ as claimed by the World Bank and the company men. For example, at least one 500-negawatt power plant could be built every year by the money spent as subsidy for purchasing gas from the international oil companies. It is increasing as their share is growing.

2. While BAPEX and Petrobangla spend Tk 1 billion to drill a well, the international oil companies do the same at a cost two to six times higher. This contradicts the argument usually given that the companies are more efficient and would reduce the cost of production.

3. We now purchase gas from national companies at Tk 25 per thousand cubic feet. On the other hand, we are purchasing the same amount at a price (in foreign currency) 8 to 10 times higher from the international oil companies in onshore blocks. Now the price is increasing further. Recent deals in offshore make this 20 times more.

4. Successive governments have periodically increased gas and electricity price to reduce subsidy caused by increasing IOC share. Rising cost of production and of living are the obvious outcomes.

5. Bangladesh lost 550 billion cubic feet of gas due to the blowout in Magurchhara (June 14, 1997) and Tengratila (January and June 2005). This amount of gas equals to gas used for power generation for more than 2 years for the whole of Bangladesh. These two blowouts hit hard the myth of IOC efficiency.

6. Compensation due from the Chevron of the United States and Niko of Canada for these disasters is yet to be realised fully. The import price of the gas lost in Magurchara and Tengratila amounts to more than $5 billion, which is nearly eight times the average yearly budget allocation for the energy sector. No government since 1997 has taken any step to realise the compensation. On the contrary, reports reveal their opposite role. It is also worth mentioning that the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and other international financial institutions that used to be very vocal about everything have remained silent for long about the compensation issue.

All relevant facts show that, by leasing out most of the resource-rich gas onshore blocks to the multinational corporations, Bangladesh has become a hostage. The cost of production of gas and electricity, and thus fiscal burden, has increased at a linear rate. Instead of saving public money, drainage and corruption increased manifold. In the guise of development increasing burden has piled up on the country and the people.

Deals on offshore blocks are going to multiply the already existing burden. On February 17, two production sharing contracts were signed with the Indian public sector oil and gas company ONGC Videsh under revised PSC-2012. The ONGC was awarded two shallow water blocks SS-04 and SS-09 in the Bay of Bengal. According to the agreement, the Indian company will spend $103.2 million during the initial exploration of the two blocks in eight years. These two blocks cover nearly 14,000 square kilometres in bay.

Earlier, on June 16, 2011, Petrobangla signed production sharing contracts with the US Company ConocoPhillips for two deepwater gas blocks — DS-10 and DS-11 — in the bay under PSC 2008. This contract gave ConocoPhillips the right to explore oil and gas from two deep-sea blocks with investment of $111 million in five years. The two blocks cover an area of 5,158 square kilometres and have a water depth of 1,000-1,500 metres.

There was strong public protest, including two general strikes in 2009 and 2011, against the deal before and after its signing. But the government continued with this.

ConocoPhillips later expressed its willingness to expand its gas exploration activities in Bangladesh and ‘requested’ the government to give it preference in the following round of international bidding for offshore gas blocks.

In PSC 2012, export provision of the earlier model was dropped, most likely to prevent further public outrage. But some cunning revision was made to ensure better deal for the companies, and worse for the country. In fact, this was revised in order to fulfil demands forwarded by the foreign oil companies. The revised document raises the price of gas almost 70 per cent to $6.50 per unit (1,000cft); provides for yearly increase; raises the share of the company concerned in the cost-recovery phase to 70 per cent of oil-gas from 55 per cent in PSC 2008, burdens Petrobangla with payment of 37.5 per cent in corporate tax on behalf of the international oil companies; and allows the international oil companies to sell its share of gas to a third party.

In sum, the latest deal makes gas and oil much costlier for Bangladesh than before. After adding all costs and taxes, it may become costlier than even imported gas. It is true that export option is not kept in PSC 2012 but export prohibition is not there either. Therefore, if gas is discovered in more than one block, and if it goes beyond 7tcf, it will be surplus for the country at a specific time. There will be no choice but to export natural gas/resources. That would certainly bring quick profit for the companies but would make Bangladesh more vulnerable to energy insecurity.

Is it the reason why the government has kept the much demanded ‘prohibition of export of mineral resources bill’ in cold storage of parliament? Is it the reason why the government silently endorsed the export option of gas resources in the national export policy? Who actually makes these decisions?

Things are not limited to oil gas deals; big projects like the Ruppur nuclear power plant without environment impact assessment, coal-based power plants by destroying Sundarban, river, wetland, are going to cause irreparable damage to the country.

When corruption and commission decides the course and nature of deals, when corporate interests dominate the ‘development’ agenda, when ‘development’ agencies and ministries turn into centre of corporate lobbyists then the country experiences ‘resource curse phenomenon’.

Because of the reign of local-global profiteers and grabbers, thus ‘development’ becomes disastrous for present and future generations. The government and the company men, in order to show these projects as TINA (there is no alternative), consistently work to block thinking and discussion on real alternatives.

The economic hit men win.

Previously published in the New Age, July 13