This post has already been read 31 times!

Share the post "International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Embedded in Business Profit, Disembedded from Nature Conservation!"

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), in its official website (http://iucn.org/), proudly describes its vision of “a just world that values and conserves nature”. Being the “leading authority on the environment and sustainable development” with “the largest professional global conservation network” operating in 160 countries, IUCN formally claims:

Our mission is to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable [emphasis added] (http://iucn.org/about/).

As long as this official mission of the IUCN involves influencing, encouraging and assisting societies to conserve nature and ensure equitable and ecologically sustainable use of nature, this organization is surely politico-economically charged. Under the circumstances, it is imperative to reflect on its genesis and examine its organizational evolution to understand how it practically operates. These exercises would help us understand whether this organization with its normative value of “just world” is functionally capable of performing its officially declared mission or operating other way round. While dealing with those issues, I argue in this essay that the IUCN since its genesis does not have this capacity and in its current form, it is more embedded in business profit than in conservation of nature.

This essay mainly has two sections. I begin the discussion by reflecting on the genesis of the IUCN and its subsequent evolution in the early years. In the second part of the essay, I justify the thematic examination of the institutional transformation of the IUCN in three subsequent sections.

Genesis of the IUCN and the Early Years

The establishment of the International Union for the Protection of Nature (IUPN) [i]/IUCN in the aftermath of the Second World War resulted from those institutional movements of nature protection that had emerged in West Europe and North America in the 18th and 19th centuries. In most cases, these movements were founded on certain discursive norms or ideological motivations. Those norms were rooted in the “imperial” idea that nature protection in the colonies meant reducing the “natives” hunting and livelihood pressures on species living there and, at the same time and in the same process, safeguarding the hunting opportunities of European hunters, and making available the enjoyment of the exquisiteness of nature to an elite of European tourists (MacDonald, 2003, p. 5; Roe, p. 493). The Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of Empire (SPWFE) established in 1903 was especially prominent in forming the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), as was the individual contribution of Julian Huxley, a long term member and president of the British Eugenics Society [ii].

Huxley’s contribution was extraordinary, as he, after becoming the first Secretary-General of UNESCO, officially patronised and promoted the organisation in its formative years. Even after the withdrawal of UNESCO funding in the mid-1960s, he played a key role in creating the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). The WWF was set up as a separate organisation to mobilise financial support of the business sector for the IUCN, and it aimed at complementing this organisational function by bringing “business leaders” into the organisation.

Huxley and the SPWFE preferred the GO-NGO hybrid model, with its partnership blending of “international intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations and national non-governmental organizations”. They felt that it would suit best to “collect, analyze, interpret, and disseminate information about ‘the protection of nature’ and to “distribute to Governments and international and national organizations documents, legislative texts, scientific studies and other information” (Holdgate, 1999, p. 34).

Unsurprisingly, given minds sensitised to the issues of colonialism, the negative connotation of the words “the protection of nature” – in the name “IUPN” and its inclination towards the exclusionary “Yellowstone Model” of national park management [iii] – generated a certain level of suspicion (Christoffersen, 1997, p. 61). Very often governments, without taking any concrete steps, were pleased to acknowledge IUPN letters suggesting technical resolutions, with a polite note that they would be “forwarded to the competent departments” (Holdgate, 1999, p. 59).

In a discursive strategy to make itself more relevant to such governments and to encourage their financial support, the organisation replaced the word “protection” with “conservation” to finally become the IUCN and, at the request of UNESCO and FAO prioritised its educational programs on the relationship between peoples and their natural and cultural settings (ibid., p. 67). The IUCN’s 1960 publication of the book Ecology and the Management of Wild Grazing Mammals in Temperate Zone – linking nature conservation with the broader context of land management – made it functionally pertinent to its government members and to UN agencies in particular.

The implementation of the Africa Special Project (ASP) ratcheted up political and public support for “ecological science based conservation practices”, and saw the preparation of a global list of parks and Protected Areas (PAs), with financial donations from FAO, the United Nations Economic and Social Council (UN ECOSOC), UNESCO, and from the WWF and USAID (ibid., p. 70, p. 72). As a consequence, field level operations in PAs for species and ecology conservation, along with education for awareness building, became the dominant themes of the IUCN in later years (ibid., p. 70).

From the start, the IUCN has seen it important to ensure that its organisational evolution marches in step with broader institutional and ideological dynamics of global political economy. For instance, when the tide of new environmentalism, rooted in the anti-industrial urban and nuclear pollution movements swept over Europe and North America in the 1960s, the IUCN took the opportunity to accommodate to the new realities. The resolutions adopted in its 10th General Assembly [iv] held in New Delhi in 1969, for example, centred around the need to address the basic causes of world environmental problems, along with its traditional goals of the conservation of nature and of natural resources (ibid, p. 108). Their shift accommodated the new environmentalism that had emerged during that period in North America and West Europe. This transformation eventually helped the IUCN obtain a grant of US$ 650,000 over the next three years from the Ford Foundation. This conformist trait of the IUCN has engendered from two structural sources: the first arises from its constant financial dependence on state and non-state donors. These stretch from UNESCO, WWF and the Ford Foundation, to environmentally harmful extractive industries like Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron and Rio Tinto, whose enthusiasm for implementing programs in the developing countries reflects their business interests. The second lies in its institutional endeavour to function across governmental and non-governmental divisions having long-term implication in its organizational evolution till today.

Three Thematic Phases of Transformation

To begin with the IUCN’s financial partnership with the business sector-oriented WWF and their collaborative program implementation was not as visible and supportive as it was to become. In those early years environmentalists and naturalists were usually inspired more by nature centred values than by pragmatic or financial interests. The regulation of harmful business and industrial activities was more of an urgent task than was furthering management collaboration with capital. Such collaboration only came to the fore for the IUCN as neoliberalism emerged in the 1980s.

In fact, the IUCN’s commitment to involving state and non-state actors in contemporary conservation co-management approaches passed through at least three phases. The first phase of the IUCN’s evolutionary progress towards a multi-stakeholder collaborative approach began in the late 1960s with the aim of linking economic development with nature and natural resource conservation through the idea of “eco-development”. The second phase came into existence with World Conservation Strategy (WCS) of the IUCN’s emphasis on local participation and empowerment under the rubric of “sustainable development”, which led business actors to emerge as “stakeholders” with their own participatory demands and status. The third phase saw the emergence of adaptive co-management as the way to further the ends of nature, justice, profit and democratic participation.

The following discussion reviews this three-stage organisational progress in the history of the IUCN, seeking to better appreciate its logic and its culmination in the multi-stakeholder participatory adaptive co-management approach of today.

i. Development-conservation linkage and eco-development s

The shift in the external settings of the environmental and conservation movements of the 1970s provided the initial ground for the IUCN to link development and conservation.

The process started with the role the IUCN played in two UN organised events: the launching of UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) programme of 1971, and the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment of 1972. The first tied nature conservation to human material needs, while the second broadened the conservation agenda with its inclusion of topics like human settlements, desertification, forestry, agriculture, water supply and tropical eco-system management. The major contribution of the Stockholm Conference was in weakening the dominant view of environmentalist/naturalists that the environment and development were at loggerheads. It succeeded because of the oil and energy entrepreneur, and president of the Canada-based Power Corporation turned Secretary General Maurice Strong’s personal interest and enthusiasm for bringing the environment within the ambit of development concerns. [v]

The IUCN had a similar theme when it held its 1972 General Assembly, Conservation for Development (Roe, 2008, p. 494). The IUCN program and the resolutions of the Assembly emphasised the importance of addressing development issues on the basis of ecological principles. The development of biotic communities, the need for assistance for the development of world network of national parks and PAs, and the economic and social value of wildlife and wild places, received priority in designing new programs (Hodgate, 1999, p. 117). In addition, the IUCN’s book, Ecological Principles for Economic Development, saw it converge with FAO, UNESCO and the UNEP, and with the business sector led WWF, in viewing conservation as “the rational use of the earth’s resources to achieve the highest quality of living for the mankind” (Dasmann et al, 1973).

With this in place it was easy for Maurice Strong, who had become the first Secretary-General of UNEP after the UN’s Human Environment Conference, to establish a strong mutual relationship between UNEP and the IUCN. This relationship enabled UNEP to take advantage of the IUCN’s already established network of professional experts through its Scientific and Technical Commissions [vi] for implementing and advocating its environmental policies and practices in developing countries. The growing operational engagement of the IUCN with UN agencies (UNESCO, FAO, and UNEP) saw accusations by the US-based the Sierra Club and an NGO forum, the American Committee on International Wildlife, that the IUCN had assumed too much of a “government character” (Holdgate, 1999, p. 125).

The IUCN’s shift of focus along this development-conservation axis was prompted and encouraged by its financial constraints, anxiety about which was spurred by the impending end of Ford Foundation funding. This worry saw the IUCN approach Maurice Strong again on the eve of the Stockholm Conference to persuade the Ford Foundation to continue their financial support. He also helped the IUCN obtain financial support from the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation, and to establish a more stable financial partnership with the WWF. All this contributed to the increase of IUCN funds from US$ 350,000 to 3.5 million during the years 1969-1976 (ibid., p. 119).

Financial worries resurfaced after Strong’s departure, and an organisational debacle that took place at 1975 General Assembly meeting saw the WWF disinclined towards further funding. The debacle erupted from concerns over the operational costs of the IUCN [vii] which were four times more than the expenditures made on conservation programs, and over the demand that more funding be at the disposal of the Commissions. These issues led to an amendment to the IUCN’s future program and budget, incorporating Strong’s idea of eco-development, the increased importance it placed on local participation in the rural development sector, and so on decentralisation and local empowerment. These dimensions of decentralisation and local empowerment were incorporated in IUCN programs, coinciding with the UN General Assembly’s (UNGA’s) 1975 adoption of a recommendation to the effect that indigenous people’s participation and traditional rights be considered for the management of national parks and other PAs (ibid., p. 125; Roe, 2008, p. 494).

On top of everything, further financial worries led the IUCN to draft Strong onto the Executive Council, and saw him elected chairman of the IUCN’s Bureau with the aim of “contributing his experience and expertise as a businessman” (Holdgate, 1999, p. 136). Strong’s co-option by the IUCN contributed to an increase in funding from the WWF and UNEP in the following years, and saw the 1978 General Assembly in Ashkabad hand the management department of the WWF, with its responsibility for managing all field projects in Asia, Africa and Latin America, over to the IUCN and its Secretariat (ibid., p. 139). In collaboration with the WWF and other members of the technical commissions, the IUCN established the Conservation for Development Center (CD) with an initial grant of an amount of US$245,000 from the Ford Foundation. It was also able to play a full partner’s role in the Eco-Systems Conservation Group (ECG) formed by UNEP in 1979 in alliance also with the UNESCO and FAO (ibid., p. 146, p. 157).

ii. Sustainable development, community participation and empowerment

Despite its efforts to tie development issues in with those of nature conservation, and its increasing financial support, the IUCN still faced criticism from many development and donor organisations, including the WWF. Those organisations slammed the IUCN for its failure to “understand what the development constituency was like” and for not “see[ing] that development was the driving force in human affairs” (ibid., p. 123). In response, the IUCN 1980 WCS, sought to meet such charges by deploying the notion of sustainable development. The task was:

[T]he management of human use of the biosphere so that it may yield the greatest sustainable benefit to present generations while maintaining its potential to meet the needs and aspirations of future generations. Thus conservation is positive, embracing preservation, maintenance, sustainable utilization, restoration and enhancement of the natural environment’ [emphasis added] (IUCN, 1980).

The WCS was based on three fundamental principles for conservation: that vital ecological processes and life-support systems be maintained; that genetic diversity be preserved; and that any use of species and ecosystems be sustainable.

The Bali Action Plan, adopted during the 3rd World Parks Congress of the IUCN in 1982, reflected this new definition of conservation, which it called a “revolutionary” advancement because of the way it connected PA conservation with an emphasis on social and economic development through local participation. This came to be labelled “Integrated Conservation and Development” (ICD) (Roe, 2008, p. 495; Holdgate, 1999, p. 153). The Congress campaigned for joint management arrangements for PAs, involving the local community, who were now recognised as the traditional owners (Roe, 2008, p. 495).

The WWF’s Wildlands and Human Needs Program (WHNP), funded by USAID, and covering 19 projects in Latin America, the Caribbean Islands and Africa, was one such major ICD venture. It began in 1985 with the aim of “benefit(ting) local people through income generation, land titling, enhanced access to and improved management of wildland resources and a variety of small scale community development projects… in collaboration with development-oriented PVOs” (WWF, 2000, p. 1, p. 22).

The Conservation Initiative in Uganda was another USAID funded project. The IUCN also undertook a similar program, the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) for field level operations in the Southern African Countries with USAID’s financial assistance. This conservation strategy encouraged around 30 countries to formulate national conservation strategies over the next few years.

Pushing forward the implementation of the WCS, regional offices of the Conservation for Development Centre (CDC) – which later become the Field Operations Division – established footholds in Indonesia, Kenya, Senegal, Costa Rica, Barbados, and Bangladesh. Even the WB in 1987, following the footsteps of the IUCN, initiated a National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) as a condition on those nations seeking access to its loan facilities (ibid., pp. 178-179). The WCS contributed to the transformation of the IUCN from a policy organisation into an implementing agency with the ever growing involvement of bilateral donor agencies (MacDonald, 2003, p. 9; Christeffersen, 1997; 61). One of the major achievements of the IUCN was the establishment of the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) in partnership with the WWF and UNEP.

All this institutional growth and activity contributed to project funds increasing from SFr 3,266000 in 1980 to 23,128000 in 1990, amounting to almost 63% of the total funding it received (see Table I). During the period 1970-1990, the number of state members rose from 29 to 50, government agencies from 54 to 94, national NGOs from 172 to 358, and international NGOs from nine to 37 (ibid., p. 63). The representation of developing countries and developed countries on the Executive Council improved with a change in ratio from 10:90 to 40:60 in the late-1970s (Holdgate, 1999, p. 139). [viii]

This is not to say that the IUCN had, at this stage, comfortably harmonized industrial economic growth-oriented development with environmental conservation, for there was resistance from the greener faction of its membership. This was evident in the corporate sector dominated Workshop 12, chaired by Michael Royston, the author of the book Pollution Prevention Pays published in 1979. The workshop took place during the Perth General Assembly in 1990. Allegations were made that the workshop reflected the business view, and the idea of corporate associate membership for the participation of the business sector in IUCN program was rejected by the state members (IUCN, 1991, p. 55, p. 214; Holdgate, 1999, p. 222). The Director General in the General Assembly took a different position. He emphasized the need to continue a dialogue involving the business sector, governments, and the IUCN (IUCN, 1991, 214). Published in 1991 in alliance by the IUCN, WWF, and the UNEP, and supported by a number of bilateral donor agencies and international organisations,Caring for the Earth: A Strategy for Sustainable Living,[ix]in effect simply yoked together sustainable living and conservation-for-development as follows:

[We seek to h]elp improve the condition of the world’s people, by defining two requirements. One is to secure a widespread and deeply-held commitment to a new ethic, the ethic for sustainable living, and to translate its principles into practice. The other is to integrate conservation and development: conservation to keep our actions within the Earth’s capacity, and development to enable people everywhere to enjoy long, healthy and fulfilling lives [emphasis added] (Munro and Holdgate, 1991, p. 3).

iii. ‘Sustainable living’, UN Earth Summit and the business sector

The IUCN completed its journey when, adopting its Declaration in the 4th World Protected Area and Park Congress, it called for the establishment of a network of PAs at a national level for conserving biodiversity, involving people from all sectors, along with local and indigenous communities. This call coincided with a speech by Maurice Strong, the Secretary-General of the 1992 Earth Summit, made upon receiving the World Park Congress Declaration and Action Plan from the IUCN. Strong observed that if the sustainable development of eco-systems did not serve and further standing economic interests “the accelerated rate of species loss will continue” (Holdgate, 1999, pp. 206-207). Here conservation and development do not go together as partners, rather development is visualized as the essential means of conservation.

The same neoliberal subsumption of conservation into development made its institutional mark in the texts of the two conventions; the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the UNCBD – both of which opened for signing at the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992. The UNFCC and the UNCBD – the two crucial offshoots of the UN Conference in which the IUCN played an important role in drafting, then administering – embedded the concept of sustainable development in the trade and market centric solutions of climate change crisis and biological biodiversity conservation problems. Article 3.5 of the UNFCCC, for instance, advocates developing countries side with “a supportive and open international economic system” for “sustainable economic growth and development”, and not adopt steps that “constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade” (UN, 1992, p. 5).

As well as dealing with the commercial use of genetic resources and benefit sharing, Articles 8 and 10 of the CBD formulate an obligation to establish a system of PAs to conserve “biological diversity”, replacing a general concern for nature and natural resources with the “conditions needed for compatibility between present uses and the conservation of biological diversity and the sustainable use of its components’” depending on “knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities” and on “measures … to avoid or minimize adverse impacts…” (UN, 1992a, pp. 6-7). Article 14 of the Convention made the involvement of the business sector systematically inevitable by making it mandatory for the State Parties to produce an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) prior to initiating development/industrial projects located close to, or in, environmentally vulnerable biodiversity areas. It is particularly relevant for the extractive sector.

The triple-bottom-line approach based on conservation, sustainable use and benefit sharing adopted in the CBD embodied a win-win-win faith well suited to sustainable economic growth and so to the business sector. These conventions were complemented by the non-binding and voluntarily implementing action plan of sustainable development codified in Agenda 21. This was prepared by the United Nations with the assistance of the IUCN, and adopted during the Earth Summit, and stressed partnership, and the role of the business and industry sectors, in addressing environmental issues (Holdgate, 1999, pp. 215).

The establishment of the Business Council for Sustainable Development (BCSD), the Global Environment Facility under the auspices of the WB through the process of the 1992 UN Conference, and the adoption of Agenda 21’s neoliberal economic framework, opened up four ways for the IUCN to make itself more relevant to both state and non-state actors: i) further expansion of state territorialization for biodiversity conservation in the form of PAs and other enclosures; ii) the extension of the funding base for the management of areas in which it relies heavily on multilateral institutions and private corporate organizations; iii) the development of an intellectual framework for “biological diversity” conservation of PAs; and iv) organizational restructuring to cash in on the opportunity to engage the corporate sector (Corson and MacDonald, 2012, pp. 270-271; MacDonald, 2003, p. 10).

The IUCN’s efforts to take advantage of the development/economic growth and environment linkage under the rubric of sustainable development led it to reflect on “The New International Scene and IUCN’s Place Within It” in its Workshop 10, held during the General Assembly in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1994. The issue of decentralization in the form of more regionalization and autonomy for the IUCN’s country offices, along with issues of partnership and co-management, received much attention.

Most importantly, in recognition of the reality of weakening state power in the environment-development nexus, the increasing impact of NGOs and multifaceted industry, the IUCN aimed to provide “leadership based on science” by establishing “bridges between North and South, East and West, governments and NGOs” (IUCN, 1994, pp. 78-79). The IUCN came up with a set of approaches for going forward: applying environmental economics as an essential part of its work, advocating sustainable development, undertaking partnership programs with the private sector, providing a conflict resolution forum, and developing institutional arrangements accordingly (ibid., p. 80).

The formation of a working group to introduce a “bottom up approach” – the Sustainable Use Initiative (SUI) – by the Species Survival Commission (SSC) was one of the practical organizational ventures undertaken by the IUCN to exploit the new post-Earth Summit reality (Christorffersen 1997, 62). Through all this the IUCN grew so that by the mid-1990’s it had 820 staff in the Secretariat, operating with seven regional offices, 21 country offices and 14 projected offices (Holdgate, 1999, p. 228).

At the next General Assembly Meeting, held in Montreal, Canada, in 1996, the World Conservation Union assumed a new name, the World Conservation Congress, and the Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (CNPA), became the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA). In later years it assumed responsibility for promoting best conservation practices and enhancing partnerships “for adapting protected areas to the forces of global change” (IUCN, 2005, p. 65). The implication and the significance of all this was made clear in comments made by the then Director General, David McDowell, in the Foreword of the published Congress Proceedings. He hailed it as a “unique and historic event”, and celebrated it for:

Open[ing]… doors… to the general public, to the economic and financial community, to development professionals – indeed to anyone with something to say on conservation. The aim was to make the work of the Union not only more open and transparent but also more relevant to the mainstream political agendas of our time (IUCN, 1997, iii).

The resolutions adopted during the 1996 Conservation Congress were clear evidence of the institutional intrusion of the IUCN into areas that previously were controversial.

The first Conservation Congress of the Union exploited its institutional arrangements to settle the hitherto existing controversy over the use of nature and natural resources for economic benefit and development. The resolutions, including those on forest management concessions, protected areas, minerals and oil extractions, transnational corporate compliance, and trade and the environment, ensured that the IUCN, with its objectives of “participatory democracy” and “participatory development”, emphasized its relevance to market actors, including multinational/transnational companies.

The resolutions promoted the voluntary independent certification of sustainable natural resource/forest management, eco-tourism, market-based incentives, the economic development of indigenous and local communities, and national development for the conservation of nature and natural resources. The resolutions offered the business community an institutional opportunity to get involved in conflict resolution processes concerning natural resource issues. This institutional striving to bring all “stakeholder” actors within a problem solving framework led to the adoption of the resolution on Collaborative Management for Conservation [x], recognizing the importance of “management partnerships” involving governments, NGOs, local communities, indigenous peoples, and gender and socio-economic groups (IUCN, 1997). The resolutions made it obvious that the development of an incentive-based social, political, legal, administrative, economic and technical framework was a precondition for the accomplishment of such “learning by doing” partnerships (ibid.). Although the resolution on collaborative management did not define the relevant socio-economic groups, the resolution on Environmental Trust Funds [xi] calling for the creation of public-private environmental trust funds, made it clear that these groups included international financial institutions and the “global business and philanthropic communities”.

In addition, addressing the issue of climate change, which it agreed to connect to biodiversity and IUCN program [xii], the Conservation Congress sought to add an element of flexibility to such “partnership” ventures when it called for mitigation and adaptation to climate change in terms of “technological advances, institutional arrangements, availability of financing, and information exchange” (ibid.). This was further entrenched at the 5th IUCN World Parks Congress in 2003, where the Durban Accord, approved by participants representing 144 countries, registers their commitment to “innovation in protected area management, including adaptive, collaborative, and co-management strategies” [xiii].

Two publications were central to the project of bringing business firms and corporate organizations into conservation management. One was Business and Biodiversity jointly published in 1997 by the IUCN and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). It sought to “explain why business should be involved in biodiversity debate and to suggest how to participate” (WBCSD and IUCN, 1997, p. 3). But the really crucial document was Collaborative Management of the Protected Areas published in 1996 by the IUCN Social Policy Group and authored by its head Grazia Borrinni-Feyeraband on the eve of the first Conservation Congress. Borrinni-Feyeraband offered the first institutional definition of the term “Collaborative Management”. He defines it as “a situation in which some or all of the relevant stakeholders in a protected area are involved in a substantial way in management activities” (Borrini-Feyeband, 1996, p. 12). The classification of “stakeholders” included a wide range of actors – local communities, governments, business and commercial enterprises, the IUCN itself – to be incorporated in the collaborative management of PAs world-wide (ibid., pp. 6-7).

The 1996 Conservation Congress’ conservation/development linkage was successful in getting the “attention of a larger constituency”, particularly that of the business sector (IUCN, 1997, p. 41), though, as the IUCN Chief Scientist Jeffrey A. McNeely, noted, much still remained to be done if the approach was to be entrenched. The IUCN, he said:

Need[s] to give much more attention to feeding the complexity of the biodiversity concept in easily-digested morsels to decisionmakers and the general public who are hungry for solutions to the problems of modern society [emphasis added] (ibid.).

The Conservation Congress welcomed the IUCN’s institutional progress on the issue of partnership, and its engagement of business firms in biodiversity conservation in other forum like the World Ministerial Roundtable on Biological Diversity of the Conference of Parties (COP) [xiv]. Participants in the roundtable insisted that “the private sector should work under the guidance of and in partnership with governments” (IISD, 1998, 2). Similarly, in the 2002 COP-6 to the CBD, participants decided to look for appropriate mechanisms by which to broaden stakeholder participation (UNEP, 2002, Annex 2). Finally, the type II voluntary agreements signed at the 2002 Johannesburg WSSD/UN Earth Summit set in place a managerial framework of “accountability”, “transparency” and “decentralization” which functioned to legitimate the multi-stakeholder approach.

In subsequent Conservation Congresses held in Amman (2000), Bangkok (2004), and Barcelona (2008), and also in the World Park Congress held in Durban (2003), the IUCN went ahead with its effort to look for “solutions to the problems of modern society”by embracing a two-complementary strategy. First, it continued decentralization and regionalization with the aim of corporatizing itself for the quick delivery of its services so as to attract more funds from private sector/business firms. Second, it brought to an end debate on whether to involve the corporates and business enterprises in the conservation partnership, and focused instead on how to engage them.

The trend to business sector partnering grew as the years passed, and is evident in the Acknowledgements of the Proceedings of the Congresses. From the 2nd to the 4th Congress the number of the sponsoring private and corporate organizations, along with the traditional patrons, including bilateral and multilateral donors, continued to increase. If the IUCN, in the 2nd Congress had expressed its gratitude to Sony, in the 3rd and 4th Congresses it did so to Shell, BP, Toyota, Philips, IXC solutions, SGS, BMW, and World Business Council for Sustainable Development. More importantly, mining and biodiversity began to get wider institutional attention, with the 2nd Conservation Congress passing a resolution [xv] calling on the Secretariat to prepare and adopt guidelines for oil, gas and mineral exploration and exploitation in arid and semi-arid zones (IUCN, 2001). This resolution culminated in the IUCN’s jointly published eco-system management series Extractive Industries in Arid and Semi-Arid Zones (2003).

A partnering initiative between the IUCN and International Council on Mining and Metal (ICMM) [xvi] was another major landmark in the process, and it came to fruition at the 2002 WSSD where an MoU for a 5-year cooperation agreement was signed. The objectives of the agreement were to improve the performance of the mining industry and to enhance their mutual understanding with “the conservation community” (IUCN/ICMM, 2008, pp. 11-12). This MoU followed the transformation of the Economics Unit into the Global BBP in 2003, with the declared strategy of engaging the extractive business sector – mining, oil and gas, fishing, agriculture, forestry, and financial services – with the more “ecological” – organic farming, renewable energy, and nature-based tourism.

All this made clear the IUCN’s determination to get business enterprises involved in its programs. The issue was no longer the development-environment linkage, it was rather “about conservation understanding the market place” and “more mature and cooperative working relations with the corporate sector and development of products and tools” (IUCN, 2005, p. 45; p. 15).

The CI initiated partnership scheme, the Energy and Business Initiative (EBI), originally comprised 10 members [xvii], including the IUCN, representing private business and non-governmental conservation bodies, made it clear that biodiversity conservation and market are no longer separate from each other. This impression – or conclusion – was echoed in the campaign tool, “Making Capitalism Work for Conservation”, launched before the 2002 WSSD for developing the International Finance Corporation (IFC) collaborated Kijani Initiative in Africa, which was presented as a “new private equity facility for biodiversity business.” The Greening Blue Energy partnership project was another initiative jointly undertaken in 2009 by the IUCN and the Swedish Development Agency (SIDA). This partnership provided the Germany-based multinational energy company E.ON guidance on the environmental performance of its offshore renewable energy projects by helping it prepare Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs), and EIAs [xviii].

For IUCN, these kinds of biodiversity business investments are important because “sustainable landscapes require both business plans for protected areas, and business plans are needed for biodiversity” (IUCN, 2002). And so it has come to pass. Economic growth-oriented development and conservation stand together like Siamese Twins, each alone and most especially together providing those “ecological services” a healthy Planet Earth requires. Biodiversity conservation is, in fact, a business and a business product; and the only “bad news is that, to date, not enough companies” have seen this and acted (Earth Watch Institute, IUCN and WBCSD, 2002, p. 6).

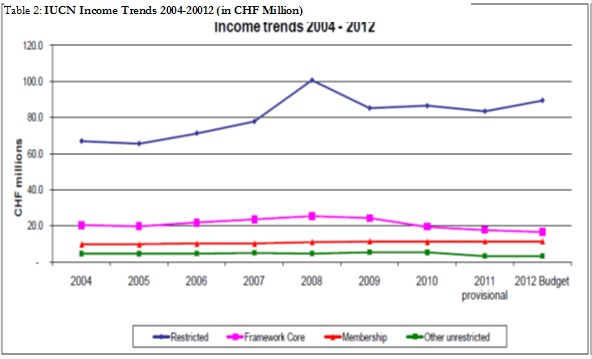

The IUCN’s co-management efforts to engage NGOs, local communities and business firms under the rubric of sustainable development transformed its original nature conservation focus. This transformation has been in step with the contemporary trend that would have us deal with climate change in terms of market oriented REDD+ solutions, clean development mechanisms, and carbon emission trading. This has contributed to an expansion of IUCN membership, which reached 1385 [xix] by 2012. The IUCNs ODA received from the bilateral donors doubled from USD 58 billion in 2000 to 106 billion in 2005, and its income increased from CHF 102 million in 2004 to 133 million in 2008 (IUCN, 2008, p. 244; IUCN, 2012, p. 472; IUCN 2012a, p. 216 ). Under the impact of the global recession which settled in from 2008/09, the Framework Income [xx] experienced a downward trend, from CHF 23.7 million to a projected level of CHF 16.5 million, demonstrating its vulnerability to the external political and economic environment (IUCN, 2012a, 216). Unrestricted income [xxi] followed the same trend (see Table 2).

These downward trends, as they did in an earlier period, have created anxiety in the IUCN. The response has been to adopt a fund raising approach, a “new business model”. This business model incorporates the idea of four business lines: flagship knowledge products; results on the ground in biodiversity conservation and nature based solutions; services for environmental policy and governance; and an IUCN with convening power and influence (IUCN, 2012, p. 479; IUCN, 2012a, p. 215). These business lines are:

[A]daptations of IUCN operations to the change in global funding opportunities and seek to package IUCN’s Program priorities in ways that enable the Union to raise the necessary resources (IUCN, 2012, p. 479).

The IUCN’s financial draft plan for 2012-2016 has targeted a particular business line [xxii]– the “Results on the ground” line with an emphasis on long term core programs – as they best way of generating funds from interested parties

One interesting example of the IUCNs application and development of this business model is to be found in the edited publication Building Biodiversity Business jointly published by the IUCN and Shell. The cover page illustration of the report aptly projects the transformation the IUCN has gone through in its partnership ventures (see figure IV-8). Readers will find it interesting to see the Shell’s logo is placed before IUCN’s. Moreover, the definition of biodiversity business given in the publication in reference to the UNCBD reveals how the desire for profit has created a common bondage between the IUCN and Shell. For Shell and the IUCN, biodiversity business is:

Commercial enterprise that generates profit through production processes which conserve biodiversity, use biological resources sustainably and share the benefits arising out of this use equitably (Bishop et al., 2008, p. 24)

The IUCN has been consistently pro-active in developing partnerships with the business sector. The signing of strategic agreements with Shell, Holcim and TATA in 2007 to help with ecosystem management in Nigeria, whale conservation around the Shakhalin Island in Russia, formulating biodiversity conservation policy in Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and the conservation of turtles in east coast of India and Lesser Flamingo on the shores of Lake Natron of Tanzania, are major examples IUCN partnership ventures with extractive industries and business firms (IUCN, 2008, pp. 51-52).

These are not the only cases of the IUCN’s collaboration with business firms. Back in 1992 the IUCN, with the financial contribution of Chevron, published La Réserve de Conkouati, Congo: Le secteur sud-ouest. Not only did Chevron operate in the Congo, it was also a regular financial contributor to the IUCN. It is no longer an issue that the IUCN and Shell agree to mutually exchange staff for “saving” Western Grey Whales in and around the energy rich Shakhalin Island, or even if Valli Mooosa simultaneously holds two posts: one as President of the IUCN, another as chairperson of Eskom, the state energy company of South Africa (MacDonald, 2008, p. 38). When business and profit matter most – living with environmental risks under the rubric of “adaptation” and “mitigation” in response to the consistent decline of domestic species and the degradation of eco-system services indicated in the IUCN’s Red List Index, the FAO’s Living Plant Index in 2009 and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment of 2005 – automatically becomes an effective approach for the Union to facilitate further “business investment” in partnership with the investors (IUCN, 2012b, pp. 5-6)!

Concluding Remarks

The IUCN is an organisation established by leading naturalists/conservationists in Northern developed countries, and it has two ways of ensuring its relevance. The first is through policy and knowledge advocacy and other organisational efforts; the second is by exploiting its GO-NGO cards in making alliances with state or with non-state counterparts, depending (of course) on the globally prevailing dominant ideological wind, as it must be, given its always pressing need for financial assistance. As a result, it has never been possible for the IUCN to go against the “conventional wisdom” that dominates nature conservation at any particular time. In other words, its normative legacy in the SPWFE and the British Eugenic Society witnessed during its birth to promote the civilian “supremacy” of the white race got every time transformed in the aftermath of the World War II only to accommodate the new global realities. It did so by constantly playing with discursive elements of nature conservation which now coincides with adaptive co-management making the business organisations and other market actors relevant in environmental policy making. But unfortunate part of this whole discursive exercise of the IUCN is that, in the process, it has got devoid of normative value of partnering even with the multinational energy companies regardless of their poor environmental records. Business profit has replaced its nature conservation value to make IUCN a perfect commercial enterprise for which nature conservation and environment are not more than commodities to sell them in the global neoliberal market so as to assume never ending financial “viability” only! Under the circumstances, it is no longer important to realise who is playing on whose ground as far as the vision of “just world” has now turned into a “just business”.

[Can be found in Identity, Culture and Politics, Vol. 15, No. 1, July 2014, pp. 72-95]

References:

Bishop, J., S. Kapila, F. Hicks, P. Hicks, P. Mitchell and F. Vorhies 2008, Building biodiversity business, Shell, IUCN, London, UK, Gland, Switzerland.

Christoffersen, L.E 1997, “IUCN: a bridge-builder for nature conservation”, in H.O Bergesen and George Parmann (eds.), Green globe yearbook 1997: yearbook of international cooperation on environment and development, Oxford University Press, Washington, USA, pp. 59-69.

Conservancy International (CI) 2009, Biodiversity corridor planning and implementation program: annual progress report, CI and USAID, Washington, USA.

Corson, C. and K.I. MacDonald 2012, “Enclosing the global commons: The Convention on Biological Diversity and green grabbing”, Journal of Peasant Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 263-283.

Dasmann, R.F., J.P. Milton, P.H. Freeman 1973, Ecological principles for economic development, John Wiley & Sons, Washington, USA.

Earth Watch Institute, IUCN, and WBCSD 2002, Business and biodiversity: The handbook of corporate action, Earth Watch Institute, IUCN, and WBCSD, Gland, Switzerland

Gevers, Ingrid, Lotje de Vries, Mine Pabari, Jim Woodhill 2008, External review of IUCN 2007: report on linking practice to policy (objective 3), annex-2 of vol. 1, Mestor Associates and Weginingenur, Ontario, Canada.

Holdgate, Martin 1999, The green webs: a union for world conservation, Earthscan, London, UK.

IISD 1998, Earth negotiations bulletin, vol. 9, no. 87, viewed 10 June 2012,

http://www.iisd.ca/download/pdf/enb0987e.pdf.

IUCN 1991, 18th General Assembly: proceedings, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

IUCN 1994, IUCN 19th General Assembly: proceedings, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

IUCN 1997, Resolutions and recommendations: World Conservation Congress, 13-23 October 1996, Gland: IUCN.

IUCN 2002, IUCN’s business and biodiversity initiative: making capitalism work for conservation, a campaign material for Kijani Initiative, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

IUCN 2005, Proceedings of the members’ business assembly, Gland, Switzerland.

IUCN 2008, Financial plan for the period 2009–2012, Congress Paper CGR/2008/17, Gland, Switzerland

IUCN 2012, Financial plan 2013–16,Congress Document WCC-2012-9.1/2, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

IUCN 2012a, Draft report of the Director General and Treasurer on the finances of IUCN in the intersessional period 2008–2012, World Conservation Congress 2012, Congress Document WCC-2012-9.1/2, Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

IUCN 2012b,IUCN’s 2013 programme: global situation analysis, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

IUCN/ICMM 2008, IUCN/ICMM dialogue review: draft final report,viewed13 July 2012, www.icmm.com/document/494.

MacDonald, K.I 2003, IUCN- The World Conservation Union: a history of constraint, viewed 10 March 2012

https//tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/9921

MacDonald, K. I. 2008, The devil is in the biodiversity: neoliberalism and the restructuring of biodiversity conservation, viewed 15 March 2012,

https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/24408/1/The%20Devil%20is%20in%20the%20Biodiversity%20-%20manchester.pdf

Munro, D. A. and M. Hodlgate 1991, Caring for the earth: a strategy for sustainable living, Glands, Switzerland: IUCN.

Osborn, F. 1937, “Development of a Eugenic philosophy”, American Sociological Review, vol. 2, no. 3, pp- 389-397.

Roe, D. 2008, “The origins and evolution of the conservation-poverty debate: a review of key literature, events, and policy processes”, Oryx, vol. 42, no. 4, pp-491-503.

Sosovele, H. 2000, East African Marine Ecoregion (EAME): socio-economic reconnaissance final report, Institute of Resource Assessment, University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salam, Tanzania, viewed 25 June 2012,

www.worldlife.org/…/coastaleastafrica/wwfBinary5783.pdf, accessed on 25 June 2012.

UNEP 2002,Report of the sixth meeting of the conference of the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, UN Doc UNEP/CBD/COP/6/20. viewed 10 June 2012,

http://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/cop/cop-06/official/cop-06-20-en.pdf, accessed on 10 June 2012.

United Nations (UN) 1992, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, New York: UN, viewed 12 December 2012,

http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf.

United Nations (UN) 1992a, United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, viewed 12 December 2012,

https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-en.pdf.

WBCSD and IUCN 1997, Business and biodiversity: a guide for the private sector, WBCSD and IUCN, Geneva, Gland, Switzerland, viewed 12 December 2011,

http://www.wbcsd.org/web/publications/business_biodiversity1997.pdf.

WWF 2000,Third year report on the matching grant for a program in wildlands and human lneeds, WWF, Washington, USA, viewed 20 June 2012,

http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PDAAY912.pdf.

Table I:Major Sources of

Funds of the IUCN (in 1000 SFr.) from 1970-1995

|

Year |

Dues |

Other |

Subtotal unrestricted |

Programme |

Projects |

Total |

|

1970 |

223 |

493 |

716 |

113 |

822 |

1651 |

|

1975 |

402 |

699 |

1101 |

294 |

2101 |

3496 |

|

1980 |

1348 |

967 |

2315 |

1893 |

3266 |

7474 |

|

1985 |

2524 |

793 |

3317 |

2199 |

7240 |

12756 |

|

1990 |

3925 |

3508 |

7433 |

6674 |

23128 |

37235 |

|

1995 |

6311 |

4093 |

10404 |

18749 |

30255 |

59408 |

Source: Christofferson, 1997, p. 66.

Source: IUCN 2012a, p. 216.

Endnotes:

[i] The IUCN, established in 1948, was originally named IUPN (International Union for the Protection of Nature). The name was changed into IUCN in 1956.

[ii] It came into existence in 1926 in Britain in light of the racist Eugenic philosophy based on the principal that human hereditary traits can be made better by encouraging more reproduction of certain superior people, and less reproduction of the people with inferior genes (Osborn 1937). [iii] It is the first national park of the world. It was established in 1972 and is located in Wyoming State at the headwaters of Yellowstone River. To establish this national park, US government native American tribes were forcibly displaced from the area. Immediately after its establishment, US Army took over its management responsibility.[iv] It is one of the IUCN’s organisational components. Two other are: the Secretariat, Scientific and Technical Commissions (six in number). General Assembly was traditionally held in every three years. But in 1996, the General Assembly was replaced with tri-annual World Conservation Congress. These organisational components of the IUCN have their own programs and divisions too.[v] He convinced the developing southern countries to take part in the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment with its avowed goal of recognising the link between nature conservation and development. He sought to allay the prevailing fears of developing countries that this was an endeavor to “ratify and even enhance existing unequal economic relations and technical dependence, miring them in poverty forever” (Hecht and Cockburn, 1992, p. 849; Roe, 2008, pp. 493-494).[vi] They now include the Commission on Ecosystem Management (CEM), the Commission on Education and Communication (CEC), the Commission on Environmental Law (CEL), the Commission on Environmental Economic & Social Policy (CEESP), the Species Survival Commission (SSC), the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA).

[vii] 80% of its budget during that was spent on staff management and salaries (Holdgate, 1999, p. 132). The salary scale was equivalent to that of UN staff’s.

[viii] The WCS focus on sustainable development and the focus on the sustainable use of biological resources in the subsequent General Assembly of the IUCN in Perth were boosted by the WCED. WCED’s definition of the term “sustainable development” in its report Our Common Future’s (1987) echoed a similar approach to that of the IUCN.

[ix] The bilateral organisations included the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the Canadian Wildlife Federation, the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), the Finnish International Development Agency (FINNIDA), the International Centre for Ocean Development, the Ministere de l’Environnement du Quebec, Ministry of Environment of Quebec, The Johnson Foundation Inc., the Ministero degli Affari Esteri, Direzione Generale per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo, Italy, the Netherlands Minister for Development Cooperation, the Royal Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). Inter-governmental and International organisations involved included the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), the International Labour Office (ILO), the ICHM-Istituto Superiore di Sanita, the Secretariat- Organization of American States (OAS), the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), UNESCO, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the WB, the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), and the World Resources Institute (WRI).

[x] Resolution No. 1.42 of the Congress.

[xi] Resolution No. 1.60 of the Congress.

[xii] Resolution No. 1.72 of the Congress.

[xiii] Durban Accord, viewed 25 June 2012, http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/durbanaccorden.pdf

[xiv] It is the governing body of CBD responsible for its implementation by convening periodic meetings for taking decisions.

[xv] Resolution No. 2.57 of the Congress.

[xvi] It is an association of 22 leading extractive industries and 34 national and regional, and global commodity associations. It was set up on 2001 to improve sustainable development performance in the mining and metals industry. The notable mining companies engaged in ICMM include Rio Tinto, AngloAmerican, BHPbilliton, AngloGold Ashanti, and Sumitomo Metal Mining.

[xvii] They include BP, ChevronTexaco, Enron, Shell and Statoil from the energy sector, and CI, Fauna & Flora International, the IUCN, The World Conservation Union, the Smithsonian Institution and The Nature Conservancy from the conservation sector. Enron, since 2001, is no longer part of the Initiative.

[xviii] IUCN website, viewed 28 June 2012, http://www.iucn.org/about/work/programmes/marine/marine_resources/projects/greeningblueenergy/

[xix] National NGO: 868; International NGO: 101; Affiliate: 43; State: 88; Government Agency with State Member: 97; Government Agency without State Member: 26 (IUCN website, viewed 12 June 2012, http://www.iucn.org/about/union/members/who_members/members_database/).

[xx] Framework income is the financial contribution made by the framework members in the form of ODA.

[xxi] It is the project/program income of the IUCN.

[xxii] Each business line contains these components: valuing and conserving nature; effective and equitable governance of nature’s use; deploying nature-based solutions to global challenges; supporting Union governance and development; operations and program support.

Share the post "International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Embedded in Business Profit, Disembedded from Nature Conservation!"

This post has already been read 31 times!