This post has already been read 40 times!

Share the post "Of Trials and Errors: International vs. National — Challenges and Opportunities (Part II)"

I want to add one point regarding the climate around the war crimes trials. There will be accusations that this is a politicised process – indeed there already are such accusations. Persuasive rebuttal of this charge will depend not only on the impartiality and due process of the war crimes trials themselves, but also on the extent to which the general climate prevailing in Bangladesh is seen as one of tolerance of political differences, past and present, consistent with principles of pluralism, multi-party democracy and respect for the role of a free civil society. And just as continuing impunity for past crimes undermines respect for rule of law in the present, so too impunity for human rights violations today will undermine the credibility of the process of justice for the crimes of the past.

– Ian Martin. ‘Forty Years On: Memory and Justice’, Anniversary Lecture, Liberation War Museum, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 22 March 2011

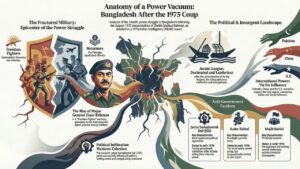

Responding to sustained popular demand, one of the promises of the AL during its election campaign in late 2008 was to bring to justice those responsible for the war crimes committed during the liberation war of Bangladesh in 1971. There were some delays in implementing this promise during its first year in government.

The Law Commission initiated a consultation process in early 2009 in which various law faculties and prominent law firms, including Abdur Razzak’s firm were requested to provide comments to review the 1973 Act for necessary amendments. While not many experts responded to the call, following these consultations, the Act was subsequently amended in July 2009.

(The consultation report can be found online at http://www.lawcommissionbangladesh.org/reports/87.pdf ).

In 2009, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) also asked the UN for technical assistance. However, there is some confusion about the process and the outcome. Some experts (name withheld for confidentiality reasons) maintain that the UN failed to respond and had subsequently abandoned the process due to Pakistan’s strong lobbying at the UN with substantial behind the scene support from campaigners in the US and France (see Wikileaks for these communications).

On the other hand, reports from the media and various international organisations indicate that members of the international community reached out to assist in ensuring a fair, domestic trial process. By international community, throughout the essay I refer to the UN; state parties such as the US, UK, Australia and those who have their own transitional justice mechanisms such as Cambodia, East Timor, South Africa, Sierra Leone, Liberia; supranational and intergovernmental institutions such as the European Union; organisations and networks such as the Human Rights Watch-HRW, Amnesty International-AI; and prominent individuals of the global civil society.

Communication from the UN for example, since mid 2009 addressed to the GoB (the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs and the Ministry of Home Affairs) noted concerns about the provision of death penalty, the full guarantees of the right to a fair trial and the protection of victims and witnesses. Offers were also made by the UN to provide technical and financial support to a Bangladesh technical mission to visit countries and institutions with applicable experience, critical information, including lessons on procedure for national war crimes trials, and alternative forms of justice as well as information.

In part, due to highly organised lobbying from the Defence strategists and also in part due to a lack of transparency by the GoB in explaining how the alleged war criminals were detained, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention on 23 November, 2011 adopted opinions that ‘the deprivation of liberty of Motiur Rahman Nizami, Abdul Quader Molla, Mohammad Kamaruzzaman, Ali Hasan Mohammed Mujahid, Allama Delewar Hossain Sayedee and Salhuddin Quader Chowdhury is arbitrary and constitutes a breach of article 9 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, falling into category III of the categories applicable to the cases submitted to the Working Group’ (UN General Assembly, HRC/WGAD/2011/66).

Both the Special Rapporteurs on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers and on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances sent urgent appeals, including those on 3 October 2012, 16 November 2012 and 5 February 2013 asking for clarifications with regard to the proceedings of the ICT. To date, there has been no formal response from the GoB.

Contrary to public opinion in Bangladesh that the international community has been indifferent to this renewed call for justice, these appeals recognised victims’ rights to justice. Unfortunately, the GoB gave signals that were generally interpreted, as ‘this is our domestic process, stay out of our business’.

Foreign Minister Dipu Moni, following the first verdict stated, ‘It needs to be clarified that this justice process was never part of any intervention by the international community, nor a result of any international compromise, unlike most justice initiatives of its kind that have taken place in the international arena’ (Opening Statement by Hon’ble Foreign Minister at the Diplomatic Briefing on the Maiden ICT Judgment, 24 January 2013, available at bangladeshwarcrimes.blogspot.ch).

If this is indeed how the government feels then why is the anxiety and disappointment when the international community instead of endorsing, is commenting negatively on the trials? If these are indeed fair trials, what is wrong with ensuring transparency and inviting consultations at various steps?

This is a critical moment in Bangladesh’s political and legal history. The Bangladesh war crimes trials could be used as examples to nurture the reform of the judiciary and curb present-day impunity. The International Crimes Tribunal’s (ICT) importance in particular is tremendous in Bangladesh’s criminal justice system. It could provide exemplary guidance that would be followed in the future justice processes. The best practices that emerge from the ICT could be employed to improve the mechanisms of the domestic courts for decades to come. Instead of sending signals of indifference to the international community, it is crucial to have an exchange of ideas and experiences.

* * *

I would like to briefly add that the international community is not necessarily non-partisan in their policies, reporting and actions. For example, it has been well established that the northern development institutions (such as the NGOs, donors, universities and so on) have an unequal relationship with their Southern ‘aid’ partners (see for example, ‘the pornography of poverty’ Betty Plewes and Rieky Stuart, 2006). Bulk of the criticism of the international human rights reports comes from regimes often at the receiving end of the ‘damaging’ reports. Usually regimes are the targets of political advocacy in many countries and as such activists welcome international attention to their causes. Activists may have problems with parts of these reports but don’t prefer to publicly challenge the moral/normative high grounds of human rights, and, there is a general belief that the international human rights organisations are their allies in their particular political struggles. Taking cue from this ground reality, fewer questions have been asked by analysts/academics about biases that remain within human rights organisations such as the HRW and the AI.

In fact, in Bangladesh, experts, practitioners and activists were equally appreciative of previous HRW and AI’s various coverage of torture, extrajudicial killings, arbitrary detention, fatwa, indigenous rights and women’s rights despite those causing embarrassment to various governments.

Some of the criticisms that were raised in the international media against the HRW include solicitation of funds from influential individuals in Saudi Arabia, its reporting of the Arab-Israeli conflict which some interpret as excessively anti-Israeli, fewer reports on the extremist groups in the Middle East, and its inaccurate reporting in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Haiti, Venezuela and Honduras. Public criticisms about the AI include anti-Semitic comments from its staff, support for anti-women NGOs in Afghanistan, inaccurate reporting of the 1991 Gulf war and so on. Both organisations were criticised for close alliance with the US and the UK foreign policy priorities at various times.

The HRW, AI, International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) and International Bar Association (IBA) reports and workshops on the ICT proceedings have met with disapproval by many observers from Bangladesh and their factual inaccuracies have been pointed out (for various critiques see International Crimes Strategy Forum media archive).

By now it is also public knowledge that the defence lobby (some of the known campaigns are organised by Toby Cadman, John Cammegh, and Cassidy and Associates in the US) is very active in the international circles, trying to seek allies and providing an account of the revisionist history to the international community.

* * *

In this context of what I have explained above, why is there no visible/proactive step taken by the GoB to sensitise the international community? Why is the international community repeatedly saying that this is a political witch-hunt when in many other war crimes trials many of these institutions and individuals are actively supporting the courts?

Why is the international media so negative and publishing damaging reports without checking facts that are abundant in official records and in public memory in Bangladesh? If they are indeed checking facts, what are their sources? Who are the authors of these reports? Who are the legal experts?

How is it that the legal/human rights community and the media become the ‘experts’ of justice and not the victims who have experienced it? Is there a calculated campaign of genocide denial which has unknown sources of funds or is it a failure in Bangladesh’s part for not being able to provide substantial evidence to counter these arguments? Or both?

It is a constitutional responsibility of the GoB to ensure a fair trial. In her statement noted above, the Foreign Minister claimed that Bangladesh is succeeding in doing so. On the contrary, the press release with comments from two Special Rapporteurs issued by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) noted ‘Given the historic importance of these trials and the possible application of the death penalty, it is vitally important that all defendants before the Tribunal receive a fair trial… The Tribunal is an important platform to address serious crimes from the past, which makes it all the more important that it respects the basic elements of fair trial and due process’ (ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=12972&LangID=E).

Why is there a perception at the international level that the government is not being able to ensure a fair trial? Is there a concern internally that if fair trials were carried out then they wouldn’t deliver the desired outcome? Or is it the issue that there is not enough hard evidence to provide to the Court?

As I will explain in the last part of this essay, criminal prosecutions always require a higher burden of proof. If there is proof then why has not the prosecution team successfully manage to convince legal experts beyond any doubt that these men are guilty as charged?

I have noted in the first part of this essay (bdnews24.com, December 16, 2012) S R Pal and Serajul Haque were appointed as chief prosecutors in 1972. Both were very prominent, well respected lawyers with knowledge of international criminal law of that time. What are the qualifications of the current prosecution team?

Those who propose that the US and Israel are violating human rights, unlawfully killing opponents with drones and still have death penalty must also ask, why should we consider these bad practices always?

We really need to ask these uncomfortable questions. And we need the answers before too long.

Some could say, these questions are being asked in close-knit circles, but an open process could also show to what extent the prejudice of the international community is playing a role here and how that prejudice has been formed in the international space. The global human rights community has been an established friend in difficult circumstances. Now why are some of them turning their back on us? Simply proclaiming that these institutions do not criticise western/northern bad practices and only target southern states that they could pick on is not enough in this globalised world. Universal norms and values are equally important as culturally diverse practices and traditions.

* * *

Gono Adalat, 1992

The civil society from Bangladesh, in particular those who have substantial knowledge of the crimes committed in 1971 could be proactive and submit their own reports to the UN agencies. Without naming names, we have groups, which represent victims and survivors of 1971. These groups could provide reports with evidence of the crimes committed in 1971 to sensitise the international community. Outreach and communication is critical.

The ICT in particular could invite amicus curiae (’friends of the court’) to provide expert briefs on various legal/judicial matters, such as what are some of the concerns of the international community.

In the ECCC (Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia), an amicus curiae was provided for the Judicial Investigation opened against Kaing Guek Eav (alias ‘Duch’). In addition, the OHCHR submitted to the Supreme Court of Cambodia in June 2008 amicus curiae brief in relation to the men convicted of murdering trade union leader Chea Vichea.

Another example that comes to mind is Guatemala. In 2003, relatives of some of the disappeared filed a complaint against a former civilian army collaborator, Felipe Cusanero Coj, claiming he was responsible for the disappearance of six farmers in the early 1980s.The issue went to the Guatemalan Constitutional Court, where the OHCHR submitted a brief as amicus curiae in 2009. It drew the Court’s attention to the position under international and regional human rights law, which sets out Guatemala’s international obligations to investigate, try and punish the perpetrators of human rights violations.

In order to ensure transparency and accountability, human rights organisations could also be asked to submit their briefs. In this way, instead of alienating the international community, the ICT could engage them. Experts such as Stephen Rapp, Richard J Rogers and Ahmed Ziauddin (but note, in this last case, it is compounded by the ICT-2 showcause notice following the Skype scandal) could be formally requested to provide their amicus briefs. This would create a culture of transparency and would give more credibility to the ICT process.

There is a political culture in Bangladesh that becomes immediately defensive in the face of criticism. We have seen that in the Padma Bridge corruption case and now the country will pay a heavy price (literally) for this. There is no point in acting in a defensive manner when it comes to the war crimes trial that is taking us back to the question of Bangladesh’s sovereignty. The politics of the blame game between national and international is neither wise nor strategic. This crucial moment in history will not come back to us. We need to reach out to the international community and provide our version of the narrative-and that has to be victim/survivor centred, responsive and responsible.

And I would like to remind those who had the patience to read this whole essay, Bangladeshi analysts must carry out systematic and quantitative investigation of lives lost and other grave sacrifices made throughout the war. Those of us who specialises in quantitative analyses must step up to this task.

– To be continued

(This article is the second installment of a three-part write-up. The first part was ‘The Scars of War, Victory and Justice’. http://kathakata.com/archives/387)

First Published in BDNEWS24.COM on February 18, 2013

http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2013/02/17/of-trials-and-errors-international-vs-national-challenges-and-opportunities/

Share the post "Of Trials and Errors: International vs. National — Challenges and Opportunities (Part II)"

This post has already been read 40 times!