International media and observers of Bangladeshi politics are grappling with the question for almost two years: is Bangladesh sliding down the path of becoming a safe haven for Islamist militants with transnational connections? Recent brutal killing of Nazimuddin Samad, a social activist for liberal causes has once again brought the issue to the fore. Ansar al-Islam, the self-proclaimed Bangladesh affiliate of al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS), has claimed responsibility for the murder.

The latest killing follows the pattern of previous murders of bloggers. This neatly fits into two dominant narratives – one that highlights the failure of government to address the growing militancy and the other that insists the government is fighting for secularism.

There is no denying that the government has not succeeded in saving the lives of a number of bloggers or providing them safety. But the rhetoric of the government raises serious questions about its commitment. The comment of the Home Minister after Samad’s killing is instructive. He has practically put the blame squarely on the bloggers; he asked “Why are they [bloggers] using these kind of languages against religious establishment? In our country, we do not allow these kind of languages. It is restricted by our law.” Although such comment is not new, it seems to be getting louder in recent days. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s recent comment has made the position of the government amply clear. While attending a Bengali New Year celebration on Thursday, she came down heavily on the bloggers who criticize Islam and the Prophet. She said nowadays it has become a fashion to write something against religion as part of free thinking. “But, I consider such writings as not free thinking but filthy words. Why anyone would write such things? It’s not at all acceptable if anyone writes against our Prophet or other religions.” Additionally, the Prime Minister questioned why the government would take responsibility in case of any untoward incident for such writings. Lack of knowledge of Islam and ill-conceived remarks have featured in online comments of some bloggers but overall most of the online discussions have addressed various dimensions of religion and extremism. Indeed, these statements have annoyed a section of the supporters of the ruling party. They decry that the government is appeasing a section of radical Islamists, seemingly to dissuade them from joining the opposition’s rank. Critics, on the other hand, express concern that this is to create an excuse for adopting a heavy handedness by the government. There are allegations that in the past, militancy and terrorism have been used as a pretext to crackdown on dissenting voices. Both Islamists and secularist critics of the government have faced the wrath of the government.

The second narrative that the government is fighting a resurgent militancy is repeated ad nauseam since 2011 to portray the opposition as the façade of the militants, as a justification for shrinking democratic space, to clamp down on the opposition and to gain support of Western countries. Interestingly, until 2015, the ruling party insisted that these militants have external connections; but it made a volte face when the transnational terrorist organizations such as the AQIS and the IS claimed to have established their organizational presence in the country. The simplistic narrative that a secularist regime is fighting back militant Islamists in a Muslim majority country ignores the complexities of the political situation. What role the long standing fissure of Bangladeshi politics plays and how religion is being used by the politicians of all shades for expediency are ignored in this narrative. The war crimes trials which began in 2010 with almost unanimous support of the citizens has played a role too. It was only opposed by the Islamists, especially the JI, to save its leaders. The trials opened the possibility to bring closure to the historical pain of the nation and deliver justice. But whether the gravity of such historic tasks has been undermined by its use for immediate partisan political gains is an open question. The non-inclusive election of 2014 and the authoritarian behavior of the regime and its supporters since has restricted the space for dissension.

The absence of these issues in the discussions on the growing militancy, especially in the international media, provides an impression that there are parallel universes within the Bangladeshi political scene – one that has the militancy and militant groups and the other, mainstream politics.

Mainstream politics, so to speak, is not a single stream of events either. One stream is the relentless persecution of the leaders of the BNP, the abject failure of the BNP to reorganize and present itself as a viable opposition, its inability to address the issue of the war crimes trial and its alliance with the JI, and the timidity of the smaller opposition parties in raising voices. All of these allow the ruling party to conduct sham elections such as the ongoing Union Council elections and undermine the foundational institutions of democracy in the country. The growing number of extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, unwritten restrictions imposed on the media, and limiting public discourse accompany these events.

The other stream is the growing discontent among the populace. The pent up frustration and anger is reflected in a series of spontaneous protests in recent days. Nationwide protests against the murder of a young female cultural activist Sohag Jahna Tanu, whose body was found in a Cantonment in early March and the investigation which proceeded at a snail’s pace with no arrests and allegations of cover up, is a case in point. The resistance of the local people to a proposed coal-fired electricity plant in Bashkahli in Chittagong which left four innocent villagers dead shows how quickly situations can escalate. There is a prevailing impression among citizens that the hacking of the central bank in February was an inside job or there was an effort to cover up, because it was only addressed after being reported in the foreign press almost a month after the incident.

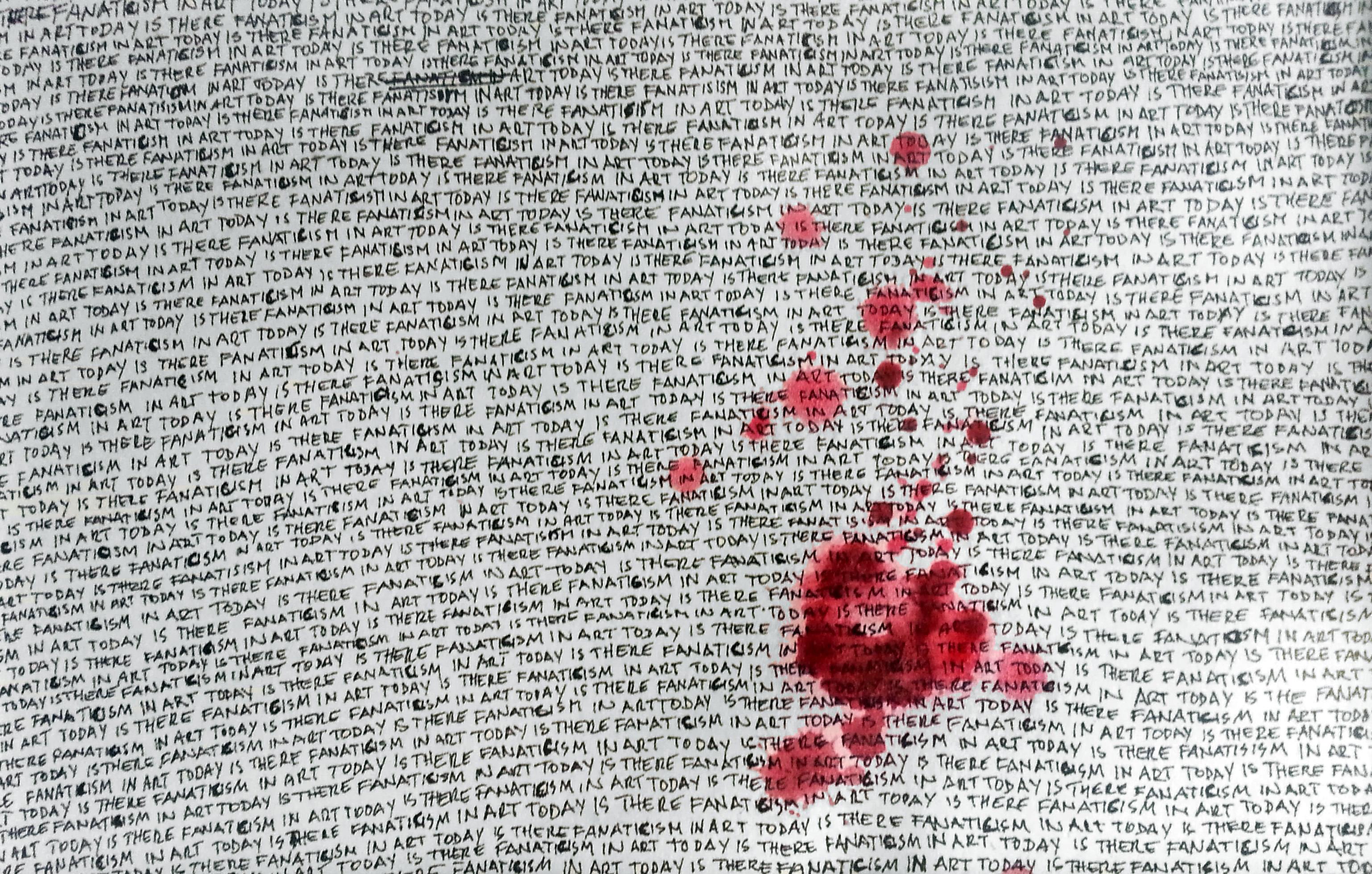

To discuss these issues in the wake of Nazimuddin Samad’s murder is unfortunate. There have been enough deaths in the past years to highlight these issues. The lessons are clear: that intolerance is breeding intolerance in society; that freedom of speech enshrined in the constitution should be applicable to all – to bloggers who criticize religious extremism, to those who express their religious faith and to others who condemn state perpetrated violence; that murder is a criminal act regardless of the twisted justifications provided for and whoever perpetrate it; that militancy should be addressed in earnest as a matter of national security; that the extant culture of impunity which discriminates between perpetrators of crimes based on their political identity must be ended; and that the absence of unfettered democracy hurts all citizens. Bangladeshi leadership and citizens can ignore these lessons only at their peril.

Published in Indian Express, 19 April 2016