Historic 36th July : Long March To Dhaka Artist: Sultan Ishtiaque

This post has already been read 46 times!

Share the post "July Uprising: Understanding the nuances of post-uprising violence to unified resistance"

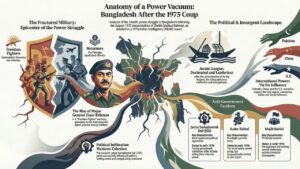

After the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s regime amid a popular uprising, her son, Sajeeb Wazed Joy, has recently made several video statements and appeared on various Indian television channels.

These communications have revealed a troubling lack of regard for the people of Bangladesh.

In one video, Joy expressed that the well-being of the population after Sheikh Hasina’s exit is of little concern to their family, suggesting an attitude that treats Bangladesh as their personal domain and its citizens as mere subjects.

In another interview, he discussed minority issues in a way that not only perpetuates falsehoods but also seems to function as propaganda in the current context.

Before exploring the specifics, it is essential to address the violence that followed the uprisings. The goal is not to justify any form of post-revolutionary or retaliatory violence but to understand it as a consequence of the regime’s long-standing oppressive actions.

Sheikh Hasina’s authoritarian and fascist rule, characterized by numerous enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, legal repression, and restrictions on freedom of expression, sparked widespread public outrage.

Rising prices, unemployment, systemic irregularities, and increasing inequality further aggravated tensions in Bangladesh, turning it into a volatile situation ready to erupt.

The severe violence perpetrated by state forces during the recent quota reform movement, which resulted in around 500 deaths, intensified this discontent.

In response, students and citizens of Bangladesh launched a spontaneous and broad-based uprising known as the July Uprisings, which took shape without the direction of a vanguard party.

Given that the uprising was a direct reaction to severe state repression and widespread violence, post-movement unrest was almost inevitable. The accumulated frustration and anger from fifteen years of oppression, compounded by recent killings over the last twenty days, led many to view Awami League leaders as public enemies.

Understanding post-uprising violence

The collapse of autocratic or fascist regimes often triggers a descent into anarchy. These regimes maintain their grip on power by systematically closing off all peaceful means of transition, which heightens public anger over time.

While attacks on police stations and the killing of Awami League leaders cannot be condoned, they can be seen as immediate expressions of decades of suppressed frustration and resentment.

Attacks on symbols associated with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and various Liberation War monuments should be understood in the context of the Awami League’s appropriation of these symbols.

Over the past decade, the Awami League has used the Liberation War and Bangabandhu’s image to legitimize its actions and consolidate its autocratic rule.

In this context, Bangabandhu’s statue has come to symbolize Awami fascism, and the narrative of the Liberation War has been co-opted as an ideological tool to maintain authoritarian rule.

Although these attacks are indefensible, they should not be mistaken for fundamentalist or anti-Liberation War sentiments, as some have suggested. Rather, they represent a rejection of symbols that have been employed to sustain a fascist regime.

Additionally, the protesters have expressed a desire to reclaim the true spirit of the Liberation War from the Awami League’s manipulation.

The violence continued beyond initial reports. Shortly after Hasina fled, there were reports of attacks on minority communities and Awami League leaders.

News of these incidents, primarily targeting Hindus, quickly spread through Indian newspapers and social media. Although Hindu shops, homes, and temples were indeed attacked in various regions, the scale portrayed in Indian media was exaggerated.

Bangladeshi newspapers have documented such incidents in at least 12 districts, where temples, homes, and shops were destroyed. These events gained significant attention, with widespread sharing on Indian social media platforms, further inflaming the narrative of communal violence.

Many of these incidents were part of a broader assault on Awami League leaders and their associates, some of whom were Hindu. Mainstream media also reported that the primary targets were individuals linked to Awami League politics.

While there were communal elements in the attacks, they are more accurately seen as a broader form of aggression aimed at the Awami League rather than purely sectarian violence.

Dangers of propaganda

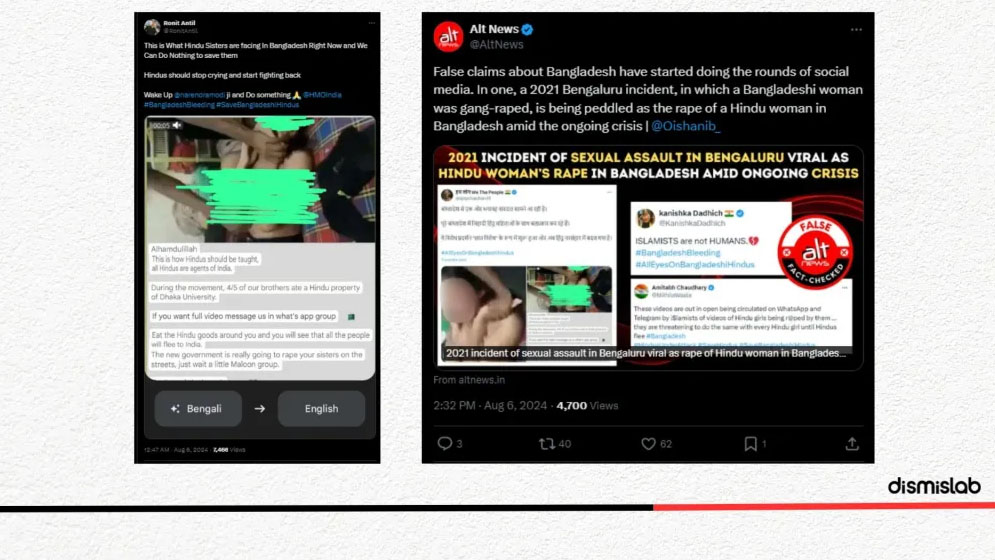

Observers have highlighted the complexities of analyzing the recent violence through a purely sectarian lens. However, the real danger lies in the spread of horrific rumors and systematic propaganda about attacks on minorities, which rapidly circulated in Indian media and on social platforms, causing widespread panic among Bangladesh’s minority communities.

For instance, rumors of attacks on temples surged on social media, though many were later proven false. Fact-checking groups have debunked some of the misinformation about widespread attacks on Hindu communities in Bangladesh during the post-movement phase.

One such rumor involved an alleged fire at the Kali Mandir in Moulvibazar, which was debunked when it was confirmed that no fire had occurred. A social media activist even posted a photo of the temple to clarify the situation.

Additionally, a student from Shahjalal University in Sylhet reported on Facebook that after hearing about an attack on the Kalibari Temple at Madina Market, several individuals went to investigate.

They found no damage to the temple or nearby homes, only some torn banners of the Jubo League, and no vandalism of shops, which had been secured in advance.

Despite the severe violence and breakdown of law and order following Hasina’s departure, the Indian media’s portrayal of the situation was notably inflated, causing significant fear and panic within the Hindu population in Bangladesh.

The West Bengal Police even addressed the situation on their official Facebook page, criticizing some local TV channels for reporting on the situation in Bangladesh in a manner that was “clearly communal and contrary to the Press Council of India’s standards.”

In this context, Joy claimed in an Indian media interview that the end of the Awami League era would lead to renewed oppression of Hindus and that without the Awami League, the Hindu population in Bangladesh would be at risk.

Joy and the TV anchor attempted to portray Hasina’s autocratic regime as a protective period for Hindus.

This comment also implies that counter-revolutionary forces have initiated attacks on people and engaged in propaganda aimed at destabilizing the country by undermining the popular uprising. Later, we will examine how the protesters themselves opposed the violence perpetrated by these counter-revolutionaries.

I am not suggesting that minorities in Bangladesh are free from oppression; rather, my point is that portraying the Awami League as a protector of minorities is deeply misleading and entirely false.

Over the past fifteen years, the Awami League has systematically targeted, occupied, and ideologically exploited minority communities, worsening their hardships.

Why is the Awami League not a protector of Hindu?

According to Ain O Salish Kendra, a leading human rights organization, there were 3,679 recorded incidents of violence against Hindus from 2013 to September 2021. These included 1,559 cases of home invasions and 1,678 attacks on religious idols and places of worship, resulting in 11 deaths.

A significant number of these attacks are linked to or perpetrated by individuals associated with the Awami League.

The most egregious example occurred during the Durga Puja festival in 2021, when a coordinated assault on Hindu temples was reportedly incited by Awami League affiliates who mobilized local Muslim communities for the attacks.

Local Awami League leaders were reportedly involved in shielding the attackers, and the administration’s ineffective response was partly due to political considerations.

Investigations into these incidents have often been obstructed, with the identities of perpetrators omitted from official reports or even promoted to public office.

Throughout its tenure, the Awami League did not prosecute those responsible for violence against minority communities; instead, these minorities were often caught in the crossfire of the party’s internal conflicts.

The Awami League has been more involved in the oppression and expropriation of Hindu land in Bangladesh than any other entity since the country’s independence.

Referring to Abul Barakat, a pro-Awami League intellectual, Jyoti Rahman noted that “over 44% of those involved in the expropriation of Hindu land were connected with the Awami League, surpassing the combined total of those affiliated with the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), Jatiya Party, and Jamaat-e-Islami.”

Advocate Rana Dasgupta, general secretary of the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Oikya Parishad, stated, “When the Awami League came to power, we hoped that communal attacks would cease. Unfortunately, not only have these attacks continued, but they have also intensified.”

While I do not dispute the occurrence of recent attacks on minority communities, I argue that we must approach the violence against Hindus with caution and a nuanced perspective.

The portrayal of the Awami League as a ‘protector of Hindus’ or a ‘friend of Hindus’ by both the Awami League’s cultural apparatus and certain segments of the Indian media is fundamentally misleading.

This narrative, which falsely ties the safety of Hindu communities to the Awami League’s rule, has caused significant distress within the Hindu community in Bangladesh.

Over the past decade, evidence indicates that the Awami League has been a major adversary of Hindus in Bangladesh, despite its efforts to garner Hindu support by invoking threats from Islamist and fundamentalist forces. This deceptive narrative continues to be promoted.

The Awami League’s cultural apparatus and some Indian media factions are actively working to undermine the recent mass uprising through targeted propaganda. They assert that without the Awami League, the nation would fall prey to fundamentalist forces—a fear the party has long exploited for political advantage.

By framing the current situation as a resurgence of Islamist extremism, this propaganda seeks to depict the Bangladeshi populace as inherently communal and to portray the uprising as driven by Islamist agendas.

Collective social resistance

The violence following the uprising is just a small part of a much larger issue. During Sheikh Hasina’s fifteen-year rule, especially in the final twenty days, a significant rift developed between the public and law enforcement.

This breakdown has led to a state of near-lawlessness, with a noticeable absence of police presence on the streets. Police stations are deserted despite the army’s assurances, highlighting the severity of the situation.

In response to reports of violence against minorities, students and protesters swiftly mobilized to counteract the violence. With the government ineffective, grassroots groups of residents have taken unprecedented steps to protect temples and homes.

Communities are self-organizing, using loudspeakers to announce that no attacks will be tolerated, including those targeting the homes of Awami League members. Collective security teams have been formed to ensure safety in these neighborhoods.

Students from various institutions, BNP activists, and members of Islamist parties have launched vigil operations in different areas, driven by fears that miscreants might attack temples.

Within a day, protesters organized themselves into patrol teams. Students from various educational institutions formed separate groups, while local youth and political activists worked together to safeguard temples and homes.

In the absence of police in urban areas, students took on traffic management duties during the day. Since Hasina’s fall, these students have continued to oversee traffic during the day and provide neighborhood security at night.

Sohid Islam, a student from a university in Khulna involved in traffic control and area protection, shared his experiences via social media.

He said, “We formed this team with students from all university departments. It has the university’s support and permission, and it has been announced on the official page.”

Support for these security teams comes from various individuals and organizations. Sohid noted, “Those involved in security and traffic management at night and other times are receiving food supplies from various voluntary organizations.”

In addition, many restaurants and private sponsors are covering the fuel and food costs for the security teams. The university has committed to providing financial support for fuel expenses, provided that receipts are submitted.

Additionally, alumni and faculty members have joined the night patrols.

While the Army and Navy are stationed in Khulna, the initial efforts by students proved more crucial than the military’s intervention. Sohid noted, “Most of the calls we receive are based on rumors, with only a one or two percent chance of an actual threat.”

Joy’s statements in the Indian media, combined with circulating rumors, are increasing panic among minorities while overlooking the widespread resistance that is developing across the country.

A revival of social engagement

This popular uprising has cultivated a new collective awareness among the populace. Under the Awami League’s regime, minorities endured attacks with police inaction and complicity from leaders.

In the current absence of government and law enforcement, people are proactively protecting temples and establishing security perimeters, transcending party affiliations. This unprecedented level of collective vigilance signifies a significant shift in public response.

Within 6-7 hours of Hasina’s departure, the student movement rapidly elevated their form of ‘resistance,’ reflecting the spirit of the July Uprisings.

While ensuring the safety of minorities in Bangladesh remains crucial, it is equally important to address the manipulative tactics employed by both Indian media and the Awami League’s cultural apparatus regarding these communities.

Previously, various neighborhood associations and organizations thrived in Bangladesh. However, during the Awami League’s fifteen-year tenure, society became highly polarized and passive, with the party infiltrating every societal level, from mosque committees to local groups.

This infiltration weakened civil engagement. In contrast, the recent upheaval has revitalized societal activity. Despite the absence of a functioning government and administration over the past two days, significant efforts have been made to prevent anticipated sabotage.

Even with the presence of police, RAB, and administrative support during the Awami League’s rule, similar issues were inadequately addressed. The July uprising has sparked a collective societal resistance against rumors and threats, including efforts to protect temples and thwart criminal activities.

This resurgence of societal engagement presents an opportunity to rebuild and strengthen community cohesion after the divisive impact of the Awami League’s fascist regime.

Bangladesh’s political parties, despite their differing perspectives, should recognize and adapt to this newfound societal spirit. They must move beyond undemocratic, family-centric structures and embrace genuine democratic principles to foster a more inclusive and effective governance system.

Orignally Published: Bangla Outlook, 13 Aug 2024

Share the post "July Uprising: Understanding the nuances of post-uprising violence to unified resistance"

This post has already been read 46 times!