This post has already been read 33 times!

There is now a tendency, emerging among legal and social analysts, to play safe with the Shahbagh movement. The reason for this is because they won’t support capital punishment in solidarity with the movement.

I argue that the Shahbagh Movement should not be identified or categorised by its call for capital punishment. Those who do so are failing to read the minds of the young bloggers who launched the Shahbagh movement, and are putting the movement at the risk of further misinterpretation.

We need to look past the call for capital punishment to judge the Shahbagh movement in its true spirit.

The motivation of those bloggers — launching the movement, risking their lives — isn’t really about the judicial killing of Quader Molla (though why not? It was there, at Nuremburg). The killing demand is not new, nor has it erupted all of a sudden. For two decades the Ghatak Dalal Nirmul Committee and other likeminded organisations have been campaigning to bring war criminals to justice. But—because of the hegemonic role played by the Awami League over them, especially after the death of Shaheed Janani Jahanara Imam—they failed to mobilise the country’s anti-war crime movement as the little known bloggers successfully did at Shahbagh. Their appeal could not transcend partisan politics.

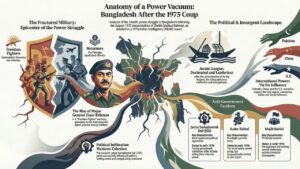

To understand what is going on we must look at those notable political events that preceded the International Crime Tribunal’s judgement on Quader Molla and the emergence of the Shahbagh movement in protest.

First, we had the murder of Bishwajit in broad daylight by activists of the student wing of the ruling party, and the controversial use of pepper spray for the first time in Bangladesh. Poor primary school teachers had to confront the brutal baton-charges and random pepper spraying. The law enforcement agencies refused to allow anti-government demonstrations in Dhaka or elsewhere in the country, and by any means.

The government did not miss an opportunity to bring the individuals to book, even for posting ‘anti-government’ or ‘anti-PM’ status in the Facebook pages. It’s policing and law enforcement was heavy-handed on any issue of political and social significance as the government saw it. And with it the growing incidence of ‘disappearance’ and extrajudicial killing of political activists and the otherwise unfavourably noticed.

The dominant powers intolerantly and repressively attacked ‘opponents’, whoever they were. The space to express political and social grievances was narrowing by the day. In this politically suffocating environment, the government played a double role when it came to confronting Jamaat-e-Islami, especially in the aftermath of the ICT’s verdict on ‘Bachchu Razakar’ case. All of a sudden ‘leniency’ towards Jamaat-e-Islami and its student wing was the order of the day. The government gave permission for them to hold political meetings and processions. In those meetings, Jamaat-e-Islami and Shibir leaders called upon its activists to wage a ‘civil war’ in the country if the ICT handed down a verdict of capital punishment on Quader Molla.

So here was a call for civil war, and what happened? What did the ruling party do? Well, even Shamsul Haque Tuku, the state minister for home affairs, openly praised the youth leadership of Jamaat-e-Islami in response to the questions, asked by the journalists at the secretariat (see the daily Prothom Alo, dated February 5, 2013, available at http://www.prothom-alo.com/detail/date/2013-02-05/news/326963)! As a result, when the ICT announced life-imprisonment for the Jamaat assistant secretary general, Quader Molla, the recently emerged rumour—that the ruling party had been in tacit political collusion with the ICT—found a foothold in the public sphere.

And the opposition party? Its traditional demand for freeing its and Jamaat’s arrested leaders conveyed the message that the two major political parties would not bring the war criminals to justice, and would continue hobnobbing with anti-Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami if they saw any political advantage in doing so.

The young bloggers exposing Jamaat’s constant denial of the liberation war did not waste the opportunity to galvanise the emotion of people against the deceptive politics of the mainstream political parties. They responded by coming down to Shahbagh in protest under the banner of the Blogger and Online Activist Network, immediately after the announcement of the judgement on Quader Molla.

The radical position of the bloggers in demanding the highest punishment available, rather than life imprisonment for the ‘Koshai Quader’ reflects and expresses the grievance and frustration the public feels at the state and its political leaders for their 42-year failure to bring war criminals to justice.

Being the self-promoted ‘pro-liberation’ force, the ruling party had little choice but to tolerate the Shahbagh movement, unlike with other ‘anti-government’ political and social movements and processions.

The nature of this movement, its non-partisan character and its lack of any central leadership, resembles the recent Occupy Wall Street movement in the USA whose ‘We are the 99%!’ rhetoric has pushed the ruling and opposition parties into a zone of political discomfort.

The moral stand of the Shahbagh movement, with its demand for justice, and for all the justice that is available (here, in Bangladesh), is what is behind the call for judicial killing, and it is a righteous call. Yet the very justice and power of the call and of those calling for it has strengthened the possibility that the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party will not side with Jamaat-e-Islami, either on the ploy of some election strategy, or on the grounds of ideological affiliation in the name of religion.

The Shahbagh movement has put all the major political parties to a double-edged sword.

The ruling elite fear that the Shahbagh movement might evolve into anti-government agitation, and so try to co-opt and control it by mobilising their own supporter-network of cultural and blogger activists.

Similarly, the demand of the Shahbagh movement to ban Jamaat-e-Islami, along with its call for capital punishment for convicted criminals, would not only deprive the BNP of a political and ideological ally, its much-propagated ideological tool of Islamic identity-based ‘Bangladeshi’ nationalism would also be in jeopardy. The position of Jamaat-e-Islami is more precarious than that of the Awami League and the BNP for an obvious reason. Losing its political power would threaten its economic enterprises. Because of these risks, the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami are trying hard to give the Shahbagh movement a colour of ‘illegitimacy’, of ‘fascism’, or of a battle for existence between ‘atheists’ and ‘believers’.

The recent killing of Ahmed Rajib Haider, an ‘atheist’ and blogger, was a calculated move on the part of whoever committed this heinous crime. The simultaneous smear campaign launched by some in the pro-Jamaat/Shibir media to portray the deceased as a ‘non-believer’ confirms two things. It confirms that the anti-Shahbagh movement forces are out to kill political opponents, even if the assassin wears religious garb, and second it shouts that we should care for each other, rather than offer a corrupt fealty to an oppressive history.

Even the poor liftman Zafar Munshi was not spared by the Jamaat-Shibir activists. If the killing of Shahbagh’s bloggers and supporters goes on, the government must know it cannot relax, if only because killing is not relaxing and systematic killing is tyranny. They must know and fear that Bangladeshis’ sentiment will turn against them for their failure to protect citizens’ lives. The lives of the bloggers who launched this movement are at risk.

For the longer it takes the ICT to finish its task, the stronger the possibility the movement will transform into an anti-government uprising, given the enormous support and solidarity it is receiving within and outside the country. In that case, the ruling elite might choose violence, and already they have made moves in this direction. Our elite will only continue to tolerate the movement as long as it remains an anti-Jamaat/Shibir movement, and presents itself as a single-issue movement concerned only with the legitimacy of capital punishment.

Then there is the fact that the sustenance and success of this movement would mean the end of the political and financial strength of Jamaat-e-Islami in Bangladesh. It would have serious political implications for the BNP as well. It would no longer be so easy or attractive for the BNP to use religion to mobilise political support. One can see why they may resort to anarchy and the killing of more bloggers and of people supporting the movement.

Given the multiple risks for the politically inexperienced bloggers, it is not the right moment to judge the Shahbagh movement in the single framework of capital punishment. The young bloggers have dared to put their lives in the line of fire, not for their personal interest, or (a version of the same thing) for becoming MPs in the next election. They are ready to sacrifice their lives for the good cause of the country they love. The demand for justice, and so for capital punishment, has given them the opportunity to come out on the street to express their grievances against the state; something not easily imaginable a few months back.

The beauty of this movement is that it is the only movement that has emerged after 1971 which points firmly to the hypocritical stand of all the major political parties towards war criminals and the misuses of religion in politics. It leaves no room for the Awami League or the BNP to remain smug, or to hope that this maverick movement will benefit them in the long run.

The success of the Shahbagh movement so far lies in the fact that our history can no longer remain ‘apolitical’. The supporters and the participants of this movement take no false pride in the statement that they do not like politics and political leaders.

We the ‘apolitical’ citizens are learning to hold and take part in political demonstrations and processions, and are exercising a new form of politics amidst multiple threats. The future of Bangladesh is taking a new route, for it has unblocked a 42-year-old repression. History can begin (again). What changes this seed brings depends on how we, the ordinary people, water it and bring it up.

We should view the Shahbagh movement as a movement against a traditional politics that abused and exploited religious sentiment for political gain. And we must not forget that the weaker our commitment to justice becomes, the stronger the anti-Shahbagh movement forces become, putting the lives of the bloggers and other supporters of the movement in an ever more dangerous situation.

Mohammad Tanzimuddin Khan is grateful to Dr Tony Lynch, his PhD supervisor at the University of New England for editing the write up.

First published on 24th February in the New Age. (Available at: http://www.newagebd.com/detail.php?date=2013-02-24&nid=40903#.USliCjfhJrR)

This post has already been read 33 times!